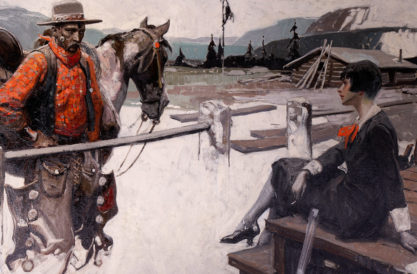

This large and evocative interior illustration by Herbert Morton Stoops was commissioned by Cosmopolitan magazine to accompany a story titled “Swans Mate” which appeared in the September 1925 edition. The briskly composed Western frontier scene shows a wild west culture war where a citified young lady encounters a rugged cowboy on the edge of the frontier. The grizzled ranch hand is either amused or annoyed with the pert, smartly attired, cigarette smoking bobbed hair flapper girl he has just come upon. Conceived with broad brush strokes which create a wonderful sense of urgency and movement. This painting was previously in the collection of and exhibited at The National Cowboy Hall of Fame and Western Heritage Center, the verso retains an exhibit label. Stoops painted in a style much like Dean Cornwell and Howard Pyle, and is a Society of Illustrators Hall of Fame Honoree.

(1888 – 1948)

Herbert Morton Stoops was born in 1888 in Logan City, Utah. At some point in Herbert’s childhood the Stoops family moved to a ranch in Idaho – then a wild, sparsely populated land, and home to the most spectacular scenery in the United States. Native American tribes roamed Idaho’s plains and mountainsides. Stoops grew up during the twilight of the Old West, amidst ranchers, miners, cowboys and Indians – larger-than-life characters who would people many of his illustrations and paintings. The open sky was his earliest canvas, and his artist’s eye studied the proportions of oxen, cattle, mules, and above all, horses – wild or tame, standing still or galloping hell for leather, it didn’t matter; Stoops was able to imbue his two-dimensional horses with a spirit of snorting, straining, three-dimensional life.

Young Herbert went on to pursue a higher education, attending Utah State College, where he graduated in 1905. In college he took his first formal art classes. This early training – added to his innate ability and the vibrant images he’d been stockpiling throughout his youth – appears to have stood him in good stead, because by 1910 Herbert Morton Stoops had already gained employment as a staff artist for the San Francisco Chronicle, and later, for the San Francisco Examiner.

In 1914, Stoops moved to Chicago, where he took classes at the Art Institute while working as a staff artist for the Chicago Tribune. He was beginning to make a name for himself as a newspaper illustrator, and was also starting to do black-and-white drawings, page decorations, and story headings for Blue Book, the literary pulp magazine with which he would be identified for the rest of his life.

But by this time the world was at war, so the budding artist enlisted in the Army, serving in France as First Lieutenant in the Sixth Field Artillery of the First Division. Stoops sent drawings from his sketchbook back to the home front. A compilation of his wartime sketches, Inked Memories of 1918, was published in 1924.

After the war, Stoops moved to New York City and married Elise Borough. Under the tutelage of Harvey Dunn, Stoops applied his early experiences to canvas and paper, becoming one of the most sought-after illustrators of his day. By the early ’20s, oils by Stoops were featured in Cosmopolitan and Good Housekeeping alongside the works of illustration giants. He began painting covers for The American Legion Magazine, a publication for which he would work constantly in the years to come.

Stoops had been a contributing artist to the pages of Blue Book previous to World War I, but editor Donald Kendicott soon took notice and assigned him a cover. In 1935 he commissioned Herbert to paint all of Blue Book’s monthly covers. Their creative collaboration would last until the artist’s death.

In 1940 Stoops received the Isidor Medal from the National Academy for his work, Anno Domini, which depicted the ravages of war on refugees. During World War II he did several posters for the office of War Information.

Stoops was working on a series of monthly covers for Blue Book when, on May 19, 1948, after a period of failing health, he died at his art studio residence on Barrow Street in Greenwich Village. He was only 60 years old but he had left a legacy of thousands of unforgettable images that had delighted the American public.

Colonel Charles Waterhouse