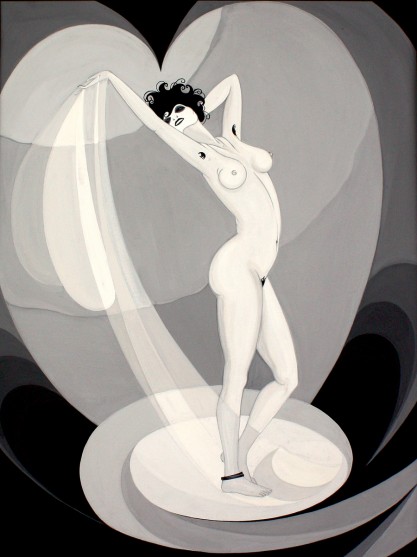

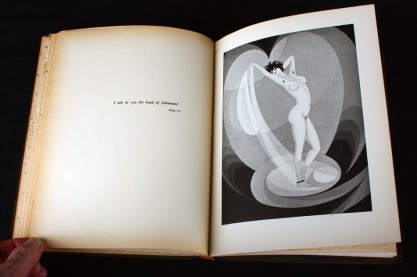

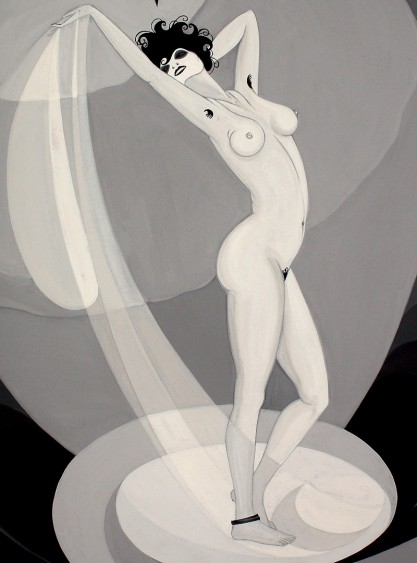

In this pivotal moment from Salome, Oscar Wilde’s notorious and classic retelling of the biblical story of John the Baptist, the romantically spurned Salome is seen ordering the beheading of Jokanaan after her erotic dance of the seven veils fails to seduce the man of God. Jokanaan is indeed executed and his head is presented to Salome on a large charger, where the daughter of Herodias is finally able to kiss the lips of her obsession. This gouache on illustration board painting was created in 1927 by John Vassos, a singularly unique inventor, industrial designer and artist and illustrator, and appeared in the E.P. Dutton & Company edition of Salome. The caption for this work reads “I ask of you the head of Jokanaan!”. Painting is handsomely framed and silk matted under glass and ready to hang.

In 1891, the notorious and wildly popular Irish poet, playwright and raconteur, first published Salome, his tragic reimagining of the beheading of John the Baptist. Immediately controversial, the play was banned on the London stage in 1893 for its sexualization of biblical characters and notable erotic content. The scandals surrounding Salome and its author, and the emotion and artistry of the play, have kept it a popular subject for illustrators. In addition to John Vassos, Aubrey Beardsley, Louis Jou, André Derain, and Valenti Angelo illustrated the tragedy, and it became an early modernist classic.

In 1923 a silent film adaptation of Salome was released, directed by Charles Bryant starring Alla Nazimova, with costume design by Natasha Rambova, who despite her marriage to Rudolph Valentino, was known to be the lover of Nazimova. Nazimova is a central figure in the history of queer Hollywood, and it is rumored that Salome was produced with only gay and bisexual actors in a homage to Wilde. The film incorporated women in drag, played with gender stereotypes, and drew upon the illustrations created by Aubrey Beardsley in the first print edition of Wilde’s play as inspiration for its design aesthetic. Vassos’s Salome, in turn, incorporates many stylistic elements from Nazimova’s creation.

Below is a film still by Arthur Rice of the film’s star Nazimova seductively dancing the dance of seven veils.

A biogrpahy of John Vassos by Jim Vadeboncoeur Jr.

Born in Greece in 1898, he spent his youth in Constantinople where he was artistically active from an early age. He served in World War I and saw action in the North Sea, at Gallipoli and as a mine sweeper. He ended up in America in 1919 in Boston. He soon was lettering placards and price tags and going to Fenway Art School at night. One of his instructors was John Singer Sargent. He spent some time as an assistant to Joseph Urban, the man who designed the famous Ziegfeld Follies. Vassos assisted on stage designs for the Boston Opera Company and designed promotional material for Columbia Records in the early Twenties.

He moved to New York in 1924 and opened his own studio, accepting any and all assignments. In his free time he attended the Art Students League and studied under George Bridgman, John Sloan and others. His modern and unique style was put to use on window displays for Macy’s and murals for two large movie palaces. This led to advertising work for New York firms like Cammeyer shoes and Bonwit Teller specialties. A restrained palette and a strong sense of design made his heavily art deco work stand out from the other commercial artists who were trying to synthesize a new, modern style to replace the staid Victorian approach of the previous 25 years.

Vassos took the black and white opaque watercolors that he’d used for price placards a few years earlier and developed his startling and powerful modernist approach that was unlike anything being done. It was immediate (to use another modern word), and a hit.

More advertising work followed – this time for national firms like Packard Automobiles and French Line cruise ships. The next step for this most “modern” of artists was simple – Industrial Design. After all, the concept of Art Deco was an offshoot of the William Morris notion of a marriage of art with industry. If wallpaper and drapes and windows could be art, why not cars and radios? And, since these were the most modern of times, why not juke boxes and fountain pens? He designed a face-lotion bottle that had one of the very first screwtop caps, just in time for Prohibition. Sales jumped. As the nation grew more crowded, he designed the ubiquitous turnstile to keep some semblance of order in our public lives.

In 1926, he was asked to create a cover illustration for a stage production of Oscar Wilde’s Salome. It was seen by an editor at the publishing house of E.P. Dutton and he commissioned a book from Vassos utilizing his distinct style. Salome was published in 1927 using a special printing technique called the Knudson Process. Later book works included Phobia, Contempo (1929), Ultimo (1930), and Humanities (1935), the artists inventions as he called the illustrations were unique and often cinematic in design. Ultimo, the text of which was written by Vassos’ wife Ruth, even tells a complete science-fictional story.

Later, as an industrial designer, the artist created packaging for consumer goods, and housing for consumer electronics. He planned the RCA pavilion at the 1939 World’s Fair, including the famous Lucite television meant to convince skeptical viewers that TV images came from the air, rather than from a miniature projector inside the set. Vassos eventually worked for RCA for more than forty years.