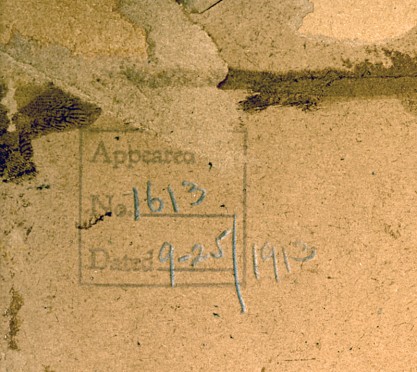

An impish winged cupid is the subject of this Edwardian Americana illustration by famed and prolific artist Orson Lowell. It appeared as the September 25, 1913 cover of Life Magazine’s Heart To Heart Number. The long running humor magazine gave this image the puckish title “A Warm Heart,” a gentle jab at America’s nostalgic and romantic obsession with cupid. In the early 20th century, the cherubic infant could be seen everywhere from cameos to magazines to early photographic art prints that showed cupid asleep, cupid awake, cupid at play, cupid at rest… Even specialty market pieces that depicted African American cupids were being produced. In this cheeky take on the phenomenon, a naked little cupid boy leaves his mark behind on a freshly painted park bench, decades later this same scenario was recast as a pin-up image by Art Frahm titled Sit Down Stripes. Painting is housed in a fine wide profile antique period frame and ready to enjoy.

The very first issue of Life Magazine that appeared in 1893 featured a winged cupid cover, and cupid figures were initially the mascot of this historic title. Below is a 1908 Life Cover illustration by James Montgomery Flagg, titled Good Vs. Evil that recently crossed the auction block in 2014 for a hammer price of $35,000.

A detailed history of Life Magazine Follows:

“Life was founded January 4, 1883, in a New York City artist’s studio at 1155 Broadway. The founding publisher was John Ames Mitchell, a 37-year old illustrator, who used a $10,000 inheritance to launch the weekly magazine. Mitchell created the first Life nameplate with cupids as mascots; he later drew its masthead of a knight leveling his lance at a fleeing devil. Mitchell took advantage of a revolutionary new printing process using zinc-coated plates, which improved the reproduction of his illustrations and artwork. This helped because Life faced stiff competition from the bestselling humor magazines The Judge and Puck, which were already established and successful. Edward Sandford Martin, a Harvard graduate and a founder of the Harvard Lampoon, was brought on as Life’s first literary editor.

The motto of the first issue of Life was “While there’s Life, there’s hope.” The new magazine set forth its principles and policies to its readers:

We wish to have some fun in this paper… We shall try to domesticate as much as possible of the casual cheerfulness that is drifting about in an unfriendly world… We shall have something to say about religion, about politics, fashion, society, literature, the stage, the stock exchange, and the police station, and we will speak out what is in our mind as fairly, as truthfully, and as decently as we know how.

The magazine was a success and soon attracted the industry’s leading contributors. Among the most important was Charles Dana Gibson. Three years after the magazine was founded, the Massachusetts native sold Life his first contribution for $4: a dog outside his kennel howling at the moon. Encouraged by a publisher who was also an artist, Gibson was joined in Life’s early days by such well-known illustrators as Palmer Cox, A. B. Frost, Oliver Herford, and E. W. Kemble. Life attracted an impressive literary roster too: John Kendrick Bangs, James Whitcomb Riley, and Brander Matthews all wrote for the magazine at the beginning of the twentieth century.

However, Life also had its dark side. Mitchell was sometimes accused of outright anti-Semitism. When the magazine blamed the theatrical team of Klaw and Erlanger for Chicago’s grisly Iroquois Theater Fire in 1903, a national uproar ensued.

Life became a place that discovered new talent; this was particularly true among illustrators. In 1908 Robert LeRoy Ripley published his first cartoon in Life, 20 years before his Believe It or Not! fame. Norman Rockwell’s first cover for Life, “Tain’t You,” was published May 10, 1917. Rockwell’s paintings were featured on Life’s cover 28 times between 1917 and 1924. Rea Irvin, the first art director of The New Yorker and creator of Eustace Tilley, got his start drawing covers for Life.

Just as pictures would later become Life’s most compelling feature, Charles Dana Gibson dreamed up its most celebrated figure. His creation, the “Gibson Girl,” was a tall, regal beauty. After her early Life appearances in the 1890s, the Gibson Girl became the nation’s feminine ideal. The Gibson Girl was a publishing sensation and earned a place in fashion history.

This version of Life took sides in politics and international affairs, and published fiery pro-American editorials. Mitchell and Gibson were incensed when Germany attacked Belgium; in 1914 they undertook a campaign to push America into the war. Mitchell’s seven years spent at Paris art schools made him partial to the French. Gibson drew the Kaiser as a bloody madman, insulting Uncle Sam, sneering at crippled soldiers, and even shooting Red Cross nurses. Mitchell lived just long enough to see Life’s crusade result in the U. S. declaration of war in 1917.

Following Mitchell’s death in 1918, Gibson bought the magazine for $1 million. But the world was a different place for Gibson’s publication. It was not the “Gay Nineties” where family-style humor prevailed and the chaste Gibson Girls wore floor-length dresses. World War I had spurred changing tastes among the magazine-reading public. Life’s brand of fun, clean, cultivated, humor began to pale before the new variety: crude, sexy, and cynical. Life struggled to compete on newsstands with such risqué rivals.

In 1920, Gibson tapped former Vanity Fair staffer Robert E. Sherwood to be editor. A World War I veteran and member of the Algonquin Round Table, Sherwood tried to inject sophisticated humor onto the pages. Life published Ivy League jokes, cartoons, Flapper sayings, and all-burlesque issues. Beginning in 1920 Life undertook a crusade against Prohibition. It also tapped the humorous writings of Frank Sullivan, Robert Benchley, Dorothy Parker, Franklin P. Adams, and Corey Ford. Among the illustrators and cartoonists were Ralph Barton, Percy Crosby, Don Herold, Ellison Hoover, H. T. Webster, Art Young, and John Held Jr.

Despite such all-star talents on staff, Life had passed its prime, and was sliding toward financial ruin. The New Yorker, debuting in February 1925, copied many of the features and styles of Life; it even raided its editorial and art departments. Another blow to Life’s circulation came from raunchy humor periodicals such as Ballyhoo and Hooey, which ran what can be termed outhouse gags. Esquire joined Life’s competitors in 1933. A little more than three years after purchasing Life, Gibson quit and turned the decaying property over to publisher Clair Maxwell and treasurer Henry Richter. Gibson retired to Maine to paint and lost active interest in the magazine, which he left deeply in the red.

Life had 250,000 readers in 1920. But as the Jazz Age rolled into the Great Depression, the magazine lost money and subscribers. By the time Maxwell and editor George Eggleston took over, Life had switched from publishing weekly to monthly. The two men went to work revamping its editorial style to meet the times, and in the process it did win new readers. Life struggled to make a profit in the 1930s when Henry Luce pursued purchasing it.

Announcing the death of Life, Maxwell declared: ‘We cannot claim, like Mr. Gene Tunney, that we resigned our championship undefeated in our prime. But at least we hope to retire gracefully from a world still friendly.’

For Life’s final issue in its original format, 80-year-old Edward Sandford Martin was recalled from editorial retirement to compose its obituary:

That Life should be passing into the hands of new owners and directors is of the liveliest interest to the sole survivor of the little group that saw it born in January 1883. … As for me, I wish it all good fortune; grace, mercy and peace and usefulness to a distracted world that does not know which way to turn nor what will happen to it next. A wonderful time for a new voice to make a noise that needs to be heard!”

“Life (magazine).” New World Encyclopedia.

Below is a list of artists that created covers for Life Magazine and some details of their contributions to the storied title:

JOHN AMES MITCHELL (1845 – 1918):

The Man Who Created Life Magazine, In addition to his formidable skills as a painter, drawer, architect and editor he also published fourteen books. Some of these were fiction, some were collections of his essays and some were collections of drawings. In his novels, and to a large extent, his other books, the major criticism seems to have been that he was somewhat over sentimental and romantic. Even in his general attitude toward day-to-day living he was called childish and sentimental.

CHARLES DANA GIBSON (1867-1944):

John Ames Mitchell who bought Gibson’s first drawing when Gibson was 7 years old said that he “detected beneath the outer badness of these drawings peculiarities rarely discovered in the efforts of a beginner…his faults were good, able-bodied faults that held their heads up and looked you in the eye. No dodging of the difficult points, no tricks, no uncertainty, no slurring of outlines…there was always courage and honesty in whatever he undertook.” He was the president of Society of Illustrators in the teens. During WWI he headed a government agency that produced war posters. He developed the beautiful ever popular Gibson girl and Gibson man.

C. COLES PHILLIPS (1880-1927):

Famous for what was known as “The Fadeaway Girl”. He used a unique technique of tying the figure into the background by texture, color or pattern. When color covers became popular his “Fadeaway Girl” made her appearance and was an instant success. He sold his first illustrations to “LIFE Magazine”.

NORMAN ROCKWELL (1894-1978):

One of the best known of all American Illustrators. His paintings of human sympathy and emotion reflect the spirit of the country during the fifty years that he graced the covers of all major magazines. Even though he is best known for his paintings for the Saturday Evening Post his work is also seen several times on the cover “LIFE Magazine”.

ALBERT D. BLASHFIELD (1860-1920):

was a personal favorite of John Ames Mitchell. He joined the staff of LIFE in the early 1890’s and remained an important illustrator until his death. His major contribution was LIFE’s cupid which floats through the pages. His style was striking and handsome but never frilly. He decorated title pages as well as in-house advertisements. He also illustrated several of Mitchell’s books.

C. CLYDE SQUIRES (1883-1970):

Born in Salt Lake City the same year LIFE Magazine was born. He published his first illustration for “LIFE Magazine at the age of 23. He is best known for his romantic depictions of the West. “C. Clyde Squires read of a researcher who drank whiskey with water and got drunk! Drank brandy with water and got drunk. Same thing happened with rum and water.

So he concluded that water was intoxicating.

“From Newspaper clipping, Albert W. Daw Collection

MAXFIELD PARRISH (1870-1966):

A unique figure in American art, not belonging to any school, part traditionalist, part inventor, sometime illustrator of gnomes and dragons, other times finding inspiration in the oak trees of his New Hampshire environs. A meticulous craftsman, Parrish’s idiosyncratic painting method involved applying numerous layers of thin, transparent oil, alternating with varnish over stretched paper, yielding a combination of great luminosity and extraordinary detail. In his hands, this method gives the effect of a glimpse through a window….except that the scene viewed is from the fairy tale world. In spite of the long time it took to perfect a painting, Parrish was prolific over the course of his productive years, from his children’s books of the turn of the century, to his famous prints of androgynous, lounging nudes during the 1920s, to his calendar landscapes of the 1930s through the 1960s.

WLADYSLAW T. BENDA (1873-1948):

Most well known for his theatrical masks. He also invented the very successful “Benda Girl”. Her success as a beautifully illustrated figure kept him working as an illustrated for most major magazines. His Polish background also made his flair for Eastern European scenes an important contribution to his illustration career. His illustrations were often a combination of pencil, ink, charcoal and watercolor or pastel.

Please Click Here for W. T. BENDA Video

WILLIAM BALFOUR KER (1877 – 1918):

William Balfour Ker possessed undoubted genius. He revolted at the

existing order of things. He was a wanderer over the face of the earth,

and voiced more dramatically than any other the cry of the unemployed. Of Mr. Ker’s nickers, as they have appeared in LIFE, it is sufficient to observe that they stand out complete in the memory, carrying the lesson of human injustice to a point where it can no longer be ignored. And what Mr. Ker’s work is, his life is: his work has grown out of his life, is the logical development of it; it expresses more beautifully and more dramatically than words the bitter cry of the underdog — portrayed with a mixture of sympathy, sentiment and humor unequaled.

F.X. LEYENDECKER (1877-1924):

Always known as the younger brother of J.C. Leyendecker. For most of his life he worked with his brother in their studio, first in Chicago and later in New York. He was born in Germany and studied for a time at the Academie Julian in France. He was known for his stained glass work as well as his illustrations for posters, magazines and advertisements. He fell victim to drugs and died in 1924.

JOSEPH CHRISTIAN LEYENDECKER (1874-1951):

The oldest of the Leyendecker brothers. Both men were famous artists. J.C. illustrated over 300 covers for the Saturday Evening Post. He also created the Arrow Collar Man. His pencil or charcoal sketches were mostly about 2×3 inches and his oils only slightly larger. He then transferred his sketches to a larger canvas by the “squaring up” method.

JAMES MONTGOMERY FLAGG (1877-1960):

He sold his first illustration to LIFE at the age of 7. He continued to work for LIFE for twenty years. His humor and satire were his forte. He worked rapidly and created many portraits and caricatures. He greatly admired women which led him to create the Flagg Girls. They were tall, wide shouldered beauties with a face as “symmetrical as a Greek vase. After an active productive life he died in virtual obscurity.

ANGUS MACDONNELL (1876-1927):

He worked for many years with LIFE Magazine as a cartoonist and illustrator. His contributions were not only color covers but double spread illustrations for the centerfold. He was first a penman in the Gibson style. Later his own distinctive style developed, characterized by two things: the beautiful use of pencil shading and the consistent nostalgic, sentimental theme. His world was that of human interest memories, wistful love and shared dreams. MacDonnell was also popular with fellow illustrators because his three daughters were popular as models.

McCLELLAND BARCLAY (1893-1943):

He was best known for the Fisher Body Girl. He worked for 10 years on this advertising campaign for General Motors. He is best known for his ability to paint strikingly beautiful women. The McClelland Barclay Fund for Art was developed after his death to aid American artists “who have never had a fair opportunity.”

ORSON BYRON LOWELL (1871-1956):

He was the son of Milton Lowell the landscape painter. He was encouraged by his father to “draw something every day”. In 1907 he became a contributor to LIFE Magazine. His social cartoons were his greatest contribution during his lengthy association with the magazine. He also illustrated many posters and books.

OTHO CUSHING (1871-1942):

He attended the Boston School of Arts and the Academic Julian in Paris. He joined LIFE in 1906 when the first cartoons he submitted received approval. His style is distinctively classical. Most of his figures use Greek Gods and Goddesses as characters. Many of his subjects are satirical comments in a political or social vein. His society women often wore togas rather than gowns. He often mixed up historical and socio-classical subjects.

ANTON OTTO FISHER (1882-1962):

He was a German orphan. As a young man he spent several years as a seaman on different vessels. Later he spent time studying in Paris at the Academic Julian in Paris. He is best known for his marine paintings. He illustrated for many of the major weekly magazines in New York. He was given the rank of “Artist Laureate” by the U.S. Coast Guard.

THOMAS KING HANNA (1872-1952):

He was a midwestern boy from Kansas City, Missouri. He attended Yale University and the Art Students League in NYC. T.K. Hanna as he signed his illustrations, worked for many of the major weekly magazines. His illustrations were skillful, strong, and “straightforward”. He rendered historic costume subjects as well as contemporary scenes.

WALTER GRANVILLE-SMITH (1870-? ):

He was from New York and studied at the Art Students League in New York City and also in Europe. He won many awards and has art work in many of the prominent New York City art clubs ie. Salmagundi Club, National Art Club and others.

JOHN HELD, JR. (1889-1958):

He was best known for his stylized flapper girls of the 20’s & 30’s. He began his career as a sports cartoonist in Salt Lake City, Utah. He taught sculpture and ceramics in his later years as an artist-in-residence at Harvard University and University of Georgia.

EDWARD WINDSOR KEMBLE (1861 -1933):

He is best known for his illustrations of southern rural life. E.W. Kemble had nor formal art training. His career began in 1881 as a cartoonist for the New York Daily Graphic. He was particularly empathetic to Black characters and “drew them with understanding”. He is known for his illustrations in books such as Uncle Remus, Huckleberry Finn and Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

B. CORY KILVERT (1881-1946):

He was devoted to watercolor seascape painting. A graduate of the Art Students League, he began as an illustrator of children’s books. For LIFE Magazine his illustrations were often on a golf theme. He was a graduate of the Art Students League.

JOHN LA GATTA (1894-1977):

He earned an early reputation for drawing beautiful women. He illustrated many magazine covers during the 19201s and 301s. In his later years he moved to Los Angeles and taught at the Art Center Collegeof Design. Herbert Andrew Paus (1880-1946) is described as full of the spirit of glorious legend. He had a strong sense of ornament with bold masterful color. He designed books, posters, cartoons and even a stage set for The Betrothal by Maeterlinck. He illustrated many children’s books and also created posters supporting the efforts of the troops during WWI. Albert Edward Sterner (1863-1946) was an English gentleman who began his career as a draughtsman and lithographer. He provided many editorial illustrations for LIFE and other popular weeklies. He taught in several NY schools and served as president of the Society of Illustrators in 1907 and 1908.

WILL CRAWFORD (1869-1944):

He was a self taught artist. He began his career in his teens illustrating for newspapers and magazines. His cartoons often poked fun at what really happened in an actual historic event. He was a free lance artist for LIFE, Puck and other weeklies. Later he moved to Hollywood and became an expert on Indian costumes.

F.G. COOPER ( ):

He is one of the worlds foremost poster artists. He is the creator of the little Edison figure and calendars. He also was a pioneer of lower case letters. During WWI he drew posters for the war and the theatre entirely in lower case letters. He used lower case letters as borders and designs in many of his covers for LIFE Magazine.

HENRY HUTT (1875-1950):

He sold his first picture to LIFE at the age of 16. His illustrations were very influential in setting fashion for the up-to-date female of the time. He studied at the Chicago Art Institute. His Henry Hutt Picture Book was a popular gift book in 1908.

VICTOR C. ANDERSON (1882-1937):

He was born into the home of Frank Anderson, a well known Hudson River School painter. From an early age he drew and painted, entering the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn. His subjects such as homespun rural life and landscapes graced the covers and center folds of LIFE for many years.

T.S. SULLIVANT (1854-1926):

He was a master draftsman who chose to distort the facts in his illustrations. His animal drawings are often a calculated exaggeration based on an intimate knowledge of anatomy.

W.A. FOGERS (1854-1931):

He was born in Ohio and by the age of 7 was drawing cartoons for a Midwestern newspaper. He moved East and took over the political cartoons from Thomas Nast for Harper’s Weekly. He would take on any kind of illustration assignment earning him the title of “special artists”.