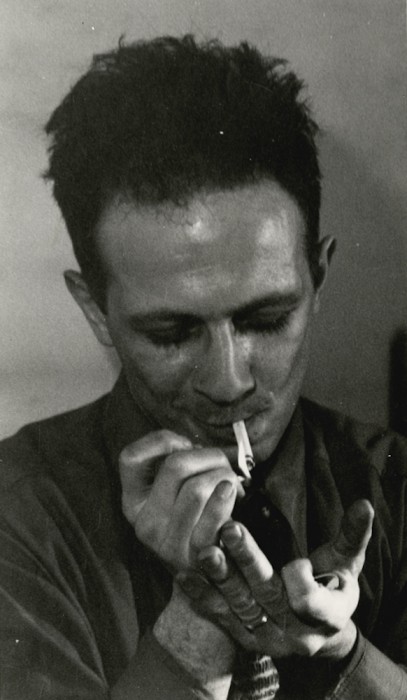

The bustling post-war world of New York City – the exciting art scene, the sometimes grimy underbelly of street life, and even the everyday, seemingly mundane, daily activities of its residents – were what drew photojournalist and painter Alfred Statler back to his home city after an extended trip abroad to refine his artistic skills.

Statler served in a European photography unit during World War II and it was there he developed his photography skills and his photojournalist / documentary style approach to his craft. Upon his return to New York City, Statler, not unlike his NYC photojournalist predecessor Weegee, preferred to capture the lively street scenes of his great city and to capture his subjects in their “real life;” at work, at lunch, or at home – participating in the seemingly mundane but captured in such an artistic style by Statler that you viewed the mundane in a whole new light. Along with photographing the everyday, Statler freelanced for some of the top periodicals of the day to photograph artists and political figures such as Elie Wiesel, Duke Ellington, Andy Warhol, and Walter Cronkite.

While Statler found much success and praise through the lens of his camera, his real talent was to be found with a paintbrush in hand. Statler started his art career as a student of Cubist master Fernand Léger in France. Statler’s interest in city life was not only to be found in his extensive portfolio of photography, but can be found in his paintings, as well. His paintings often capture urban eccentricities of life in New York City and include pronounced industrial and machine age imagery.

With just a touch of Cubist influence (a nod to his teacher Léger), Statler’s oil paintings tend to be executed in a WPA, Regionalist, and often times stark Ashcan School design aesthetic. His mesmerizing and dark style of painting of New York City traffic or masses waiting at a train station stay true to his love affair with city life and the everyday activities of the common man; depicting the struggle and and sometimes smothering difficulty of life in America after World War II.

Alfred Statler’s work alone is impressive and tells a different and more realistic artistic interpretation of life in America after the war (as opposed to the glossy and highly reproduced works of Warhol, Rosenquist, etc.), but he did not always work alone. Statler’s wife, Betty, was also a photographer and they often worked together. An artist in her own right, Betty was also drawn to New York for it’s bustling cultural environment and became almost immediately interested in photography. A photo researcher for TIME magazine, Betty was eventually allowed to go on her own photojournalism assignments which included extensive travel photographs and, more notably, her images of Mother Theresa taken in India. Later in life, Betty turned to sculpture when poor eyesight meant she could no longer photograph.

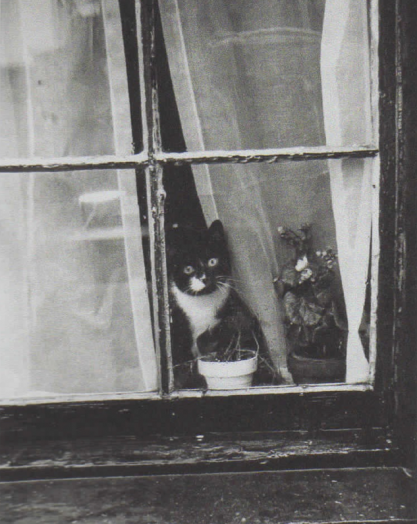

This oft-underrated, self-made, and cat-crazy photographer couple (they had an ongoing documentation of cats that were occasionally exhibited at cat adoption shelters) captured the heyday of New York’s art scene, its celebrities & intellectual elite, and the sometimes gritty underbelly of the city’s industrial core. Drawn to the city’s artistic and intellectual milieu, and to each other, the two documented New York City and their travels around the world through humanist photojournalism and stark, expressionist paintings. They are a couple more than worthy of the artistic accolades they are given in their ardent pursuit to the representation of life and industry in New York City.